I walked around Union Park wearing headphones and taking note of how police formed their response to protesters the week of DNC. I planned to walk the protests all week and wanted to be there early enough to see. So beautiful a day, and the music so engrossing, I was consumed by the work. It doesn’t happen often.

Toward the edge of the park, large speakers and loud music. Clear, crisp sound. I took my headphones off, and standing there jaded in the infield I thought: I can see the appeal of drinking all afternoon and dancing my face off into a summer night. Something I should have given greater consideration to when I was younger instead of forming this protective shell that kept me from anything that wasn’t work. This was my first time inside Union Park. The window for that is closed.

I published an essay last week, about art and violence. I finished the first draft before Thanksgiving. In the spring I felt settled, like I figured out what I had to say. I’ve been afraid to share this because it’s a deviation from the subject and form of what I normally write. I don’t think I’ll ever live without some enduring fears. It doesn’t matter whether justified. Either face it, or don’t.

I just finished the last two books by Cormac McCarthy. I have a notebook I used to write down passages instead of underlining them on the page. Most recently “Stella Maris,” and before that “The Passenger.” Maybe that will wear off, though I don’t think so … the first page of that book is among my favorite ever.

“It had snowed lightly in the night and her frozen hair was gold and crystalline and her eyes were frozen cold and hard as stones. One of her yellow boots had fallen off and stood in the snow beneath her. The shape of her coat lay dusted in the snow where she’d dropped it and she wore only a white dress and she hung among the bare gray poles of the winter trees with her head bowed and her hands turned slightly outward like those of certain ecumenical statues whose attitude asks that their history be considered. That the deep foundation of the world be considered where it has in its being the sorrow of her creatures. The hunter knelt and stogged his rifle upright in the snow beside him and took off his gloves and let them fall and folded his hands one upon the other. He thought that he should pray but he’d no prayer for such a thing. He bowed his head. Tower of Ivory, he said. House of Gold. He knelt there for a long time. When he opened his eyes he saw a small shape half buried in the snow and he leaned and dusted away the snow and picked up a gold chain that held a steel key, a whitegold ring. He slipped them into the pocket of his huntingcoat. He’d heard the wind in the night. The wind’s work. A trashcan clattering over the bricks behind his house. The snow blowing out there in the forest in the dark. He looked up into those cold enameled eyes glinting blue in the weak winter light. She had tied her dress with a red sash so that she’d be found. Some bit of color in the scrupulous desolation. On this Christmas day. This cold and barely spoken Christmas day.”

I was skeptical of “Stella Maris” because the book is dialogue, just a series of conversations, between two characters. No attribution, no breaks. It’s a companion to “The Passenger,” and it would take more effort to understand without having read that book first. In both books, lots of laughs. Comedy in his other novels but these feel different.

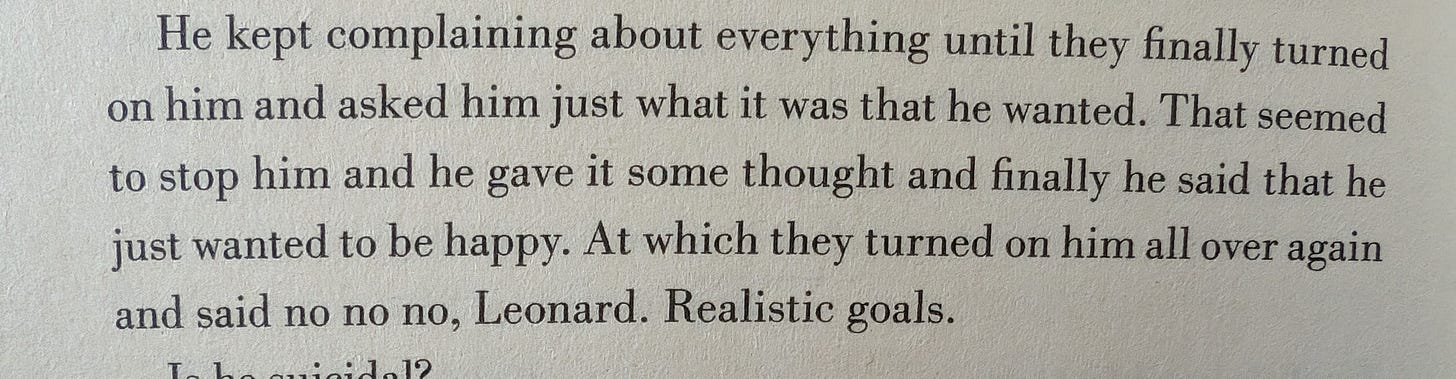

When released some reviews and reaction focused on the way math and its history is central to the story but, as someone with no comprehension there, I did not find it distracting. The book is a lot of things, among them, a love story and a reflection on sorrow and grief and a deep contemplation of suicide and the desire not just to die but to never have been.

“When all trace of our existence is gone, for whom then will this be a tragedy?”

“If you had to say something definitive about the world in a single sentence what would that sentence be? It would be this: the world has created no living thing that it does not intend to destroy.”

“Do you have troubling dreams? Is there any other kind?” “At what age in a child’s life does rage become sorrow? … the injustice over which they are so distraught is irremediable. And rage is only for what you believe can be fixed. All the rest is grief. At some point they get this.”

“I hadn’t known until that night that at its worst lust could be something close to anguish … a friend once told me that those who choose a love that can never be fulfilled will be hounded by a rage that can never be extinguished.

Are you enraged?

I don’t know. I know that you can make a good case that all of human sorrow is grounded in injustice. And that sorrow is what is left when rage is expended and found to be impotent.”“Stella Maris” is the only book I’ve started rereading as soon as I finished. Just to keep processing. After a book, though. Do you feel more whole and seen and present knowing there’s language that begins to describe emotion, or more alone by feeling more acutely result of that understanding?

Reading:

The Passenger

Stella Maris

Dinosaurs Before Dark

Listening:

The Marias

Lana Del Rey

Broken Bells

Hippie Sabotage

Nathan